This is the story of my journey with medium format. I develop all film at home and am constantly making mistakes with film, and trying to learn from those mistakes.

Medium format has given me something intangible that I don’t get with 35mm. I’ve been shooting film since the 1980’s. These days I shoot both digital and film medium format. It’s difficult to make mistakes with my Fuji GFX system, but very easy with film. Even with the problems with film, when a film negative in medium format is done right, there’s something special about it. An ethereal quality. Something I can’t quite put into words.

No one has ever taken an amazing film photo and thought “I really wish I had shot that on digital”. It’s usually the opposite, and yet medium format digital is so convenient. This is the constant struggle of choosing between film and digital.

What is Medium Format?

Medium format photography uses film or digital sensors larger than 35mm but smaller than 4×5 large format. Whether you shoot 120 roll film on a classic Hasselblad or Pentax 67, or use a modern Fujifilm GFX digital system, the larger capture area delivers more detail, smoother tonal gradations, and a distinctive depth that smaller formats can’t match.

Latest Medium Format Posts:

This site covers the full range of medium format photography — from camera reviews and film stock comparisons to home developing, scanning, and darkroom printing. Whether you’re exploring medium format for the first time or looking to refine your technique, start with the guides below.

Medium Format Camera Guides

Detailed reviews and setup guides for the most popular medium format systems, covering both film and digital.

- The Hasselblad 500cm — The iconic 6×6 system: modularity, lens options, and what to know before buying

- Pentax 67 Review — The giant SLR that changed medium format: history, versions, and shooting experience

- The Hasselblad 500 Series — A broader look at the 500 system lineup and its evolution

- Setting Up the GFX 100s — Getting started with Fujifilm’s digital medium format system

- Medium Format Camera Types — From 1901 box cameras to modern mirrorless: a complete history

Medium Format Film Photography & Developing

Practical guides to shooting, developing, and troubleshooting medium format film at home.

- Developing Color Film at Home — C-41 processing walkthrough for medium format

- Film Developing Issues — Common problems and how to diagnose them

- Streaks in Film — Causes and fixes for development streaking

- The Cost of Shooting Medium Format Film — A realistic breakdown of what it costs per frame

Medium Format Film Stocks

- Kodak Portra — The professional color standard

- Kodak Ektar — The finest grain film in the world

- Kodak Gold 200 — Budget-friendly color with character

- Ilford HP5 — A versatile black and white workhorse

The Final Print

Medium format digital scanning and traditional optical printing techniques.

- Dynamic Range of Scanned Negatives — Getting as much dynamic range as possible from a flatbed scanner with medium format negatives

- Epson V850 Scanner — A full review of this film negative scanner. plus tips and tricks for getting the best results.

- Flatbed Scanning Vs. Camera Scanning — Get help choosing which method is best for your needs.

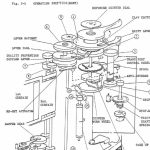

- Omega C-700 Enlarger — Setting up a medium format darkroom enlarger

- 8×10 Contact Printing — The basics of contact printing large negatives and how they compare to medium format

- Inkjet vs. Darkroom Prints — Comparing longevity and quality between digital and analog output

- How Film Is Made — Understanding what’s inside the roll

Medium Format Comparisons & Technical Deep Dives

Side-by-side tests and technical analysis across formats and systems.

- Medium Format Film vs. Fuji GFX — How film 120 negatives compare to digital medium format

- Why Does Medium Format Film Look Better Than Digital? — Exploring what gives film its distinctive look

- Adapting Pentax 67 Lenses to Fuji GFX — Quite possibly the ideal marriage of two systems

- GFX vs. Leica M — Digital medium format against a full-frame rangefinder

- GFX Resolution — Testing the limits of the Fujifilm GFX sensor

- The Brenizer Method — Simulating medium format depth of field with smaller sensors

About This Site

I’ve been shooting for over 30 years, starting with 35mm Nikon film cameras in the 1990s, moving through digital, and eventually finding my way to medium format. Today I shoot across Hasselblad 500cm, Pentax 67, and Fujifilm GFX systems, and I develop and print all my own film at home.

This site documents what I’ve learned — including the mistakes. If my missteps can save you a ruined roll or a bad scan, it’s worth sharing.